Land Capability Classification and Conservation Planning

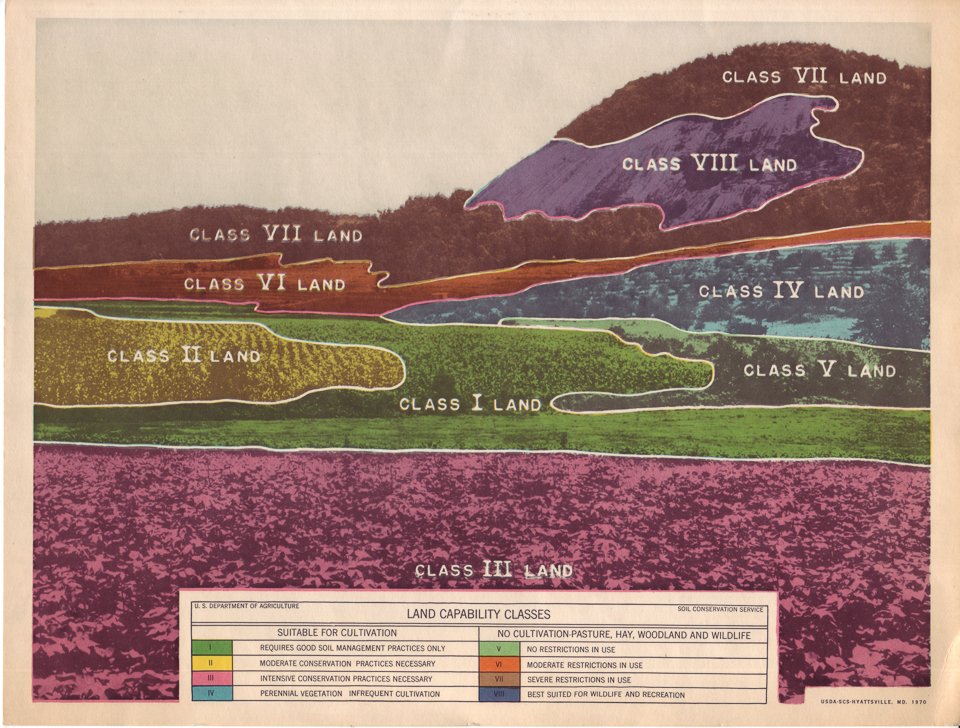

Illustration from the Soil Conservation Service showing the eight land capability classifications, 1970

Every conservation plan begins with a simple but profound question: What can this land sustain? The answer lies in the land capability classification system—an innovative framework developed in the 1930s that remains the scientific foundation of conservation planning today.

A New Way to See the Land

Before land capability classification, farmers relied on local experience and trial-and-error to decide how to use their land. The Dust Bowl demonstrated the catastrophic consequences when land unsuitable for cultivation was plowed. Hugh Hammond Bennett and the Soil Conservation Service recognized that sustainable agriculture required a scientific system for matching land use to land capability.

The breakthrough came during watershed demonstration projects of the 1930s. As SCS soil scientists mapped soils and observed erosion patterns, they developed a land classification system to guide conservation planning. It was based on permanent soil characteristics: texture, depth, slope, drainage, erosion hazard, and climate. These factors don't change with management—they define what the land can sustainably produce.

Eight Classes, Clear Choices

The system groups all agricultural land into eight classes, with Roman numerals I through VIII indicating progressively greater limitations:

Classes I-III: Suitable for cultivation with increasing conservation measures. Class I is rare—level, deep, no erosion. Class II needs simple measures like contour farming and terracing. Class III requires intensive conservation treatment.

Class IV: The critical boundary. Limited to occasional cultivation, better used permanently in grass or trees. Much Oklahoma land falls here.

Classes V-VII: Not suitable for cultivation. Should be in permanent cover—grass, trees, or managed for wildlife. Class VI and VII should never be plowed.

Class VIII: No agricultural use. Rock outcroppings, desert. Wildlife habitat only.

The Critical Principle: Capability vs. Productivity

As Sellars G. Archer, Work Unit Conservationist in Washita County, explained in 1956: "Land capability and land productivity are not the same thing." Capability describes physical properties determining sustainable use. Productivity measures current yield, which can be temporarily high even on land being destroyed by erosion.

Archer emphasized a truth conservationists learned through bitter experience: "Land cannot be upgraded, even by the best soil-building practices known—that is, not in our lifetime." Land degradation is irreversible on human timescales. After damage is done, the refrain is always the same: "this land should never have been plowed."

The goal became clear: use each acre according to its capability, treat each acre according to its needs.

Planning by Capability

Conservation planning built on this foundation. When farmers contacted their conservation district, soil conservationists reviewed the soil survey, identified capability classes across the operation, and worked with land users to develop practices matching each acre's capability.

Class I and II lands received contour farming and fertility management. Class III required terraces, waterways, and crop rotations. Class IV needed grass in the rotation most years. Classes VI and VII should return to permanent grass.

Living Legacy

Nearly 90 years after its development, land capability classification remains central to conservation planning. NRCS conservationists still use it. Conservation policy is still based on it. Students competing in the National Land and Range Judging Contest learn to assess it.

The system endures because it's based on permanent soil characteristics rather than temporary conditions. When you see terraces following hillside contours, grass waterways protecting drainage channels, or native prairie restored on marginal cropland, you're seeing land capability classification in action—the practical application of a scientific framework that transformed how America thinks about sustainable land use.

Hugh Hammond Bennett's principle remains the foundation: "Use each acre in accordance with its capability. Treat each acre in accordance with its need." This is where conservation planning begins.

Learn more about the science behind conservation planning at okconservation.org. Join OCHS in preserving the stories of the soil scientists and conservationists who developed and applied these tools to restore Oklahoma's land.